- The past week saw share markets rebound helped by optimism about a peace deal in Ukraine, a fall back in oil prices, relief that the Fed’s first rate hike was broadly as expected with the Fed seeing the US economy as strong and indications that China will provide more policy stimulus partly to combat covid related lockdowns. This saw strong gains in US, European and Japanese shares. The strong global lead saw Australian shares rise led by strength in IT, financial, telco and health care stocks more than offsetting weakness in resources shares. Bond yields rose on inflation concerns and increased expectations for rate hikes. Oil prices fell on optimism regarding a peace deal and metal and iron ore prices also fell, but all remain above pre-war levels. The $A rose as the $US fell.

- Have we seen the low in shares? After a 13% top to bottom plunge US and global shares have rebounded cutting the decline to around 8% from their bull market high. Similarly Australian shares have cut their losses from last year’s bull market high (with the market down 10% to its low in January) to around 5%. It’s possible we may have seen the lows, but uncertainty remains high around the war and inflation is still likely to get worse before it gets better keeping uncertainty high around the extent of monetary tightening. And so far the rebound in shares has lacked the breadth and strength often seen coming out of market bottoms. So, while views are that share markets will be higher on a 6-12-month horizon it’s still too early to say we have seen the bottom.

- Ukraine and Russian peace talks seem to be making some progress, but reports on this are conflicting and they have a way to go yet. With Russia now under immense pressure economically due to sanctions and with no hope of an easy victory in Ukraine and Ukraine under immense pressure from Russia a peace deal is possible based on a neutral Ukraine and Ukraine getting security guarantees. If one is reached markets would see a strong bounce, but if not, things could get a lot worse before they get better. So, Ukraine related risks for investment markets remain high in the short term.

- Oil and commodity prices seeing wild swings. After energy and commodity prices initially surged, they have since fallen on demand destruction concerns and hopes for a peace deal. When the dust settles, they are still likely to end up at levels above where they were pre-war, unless the sanctions are quickly removed. But maybe the worst-case scenarios like oil at $US200/barrel plus might be avoided. Out of interest the fall back in world oil prices means Australian petrol prices (E10) should be back around $1.9/litre.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

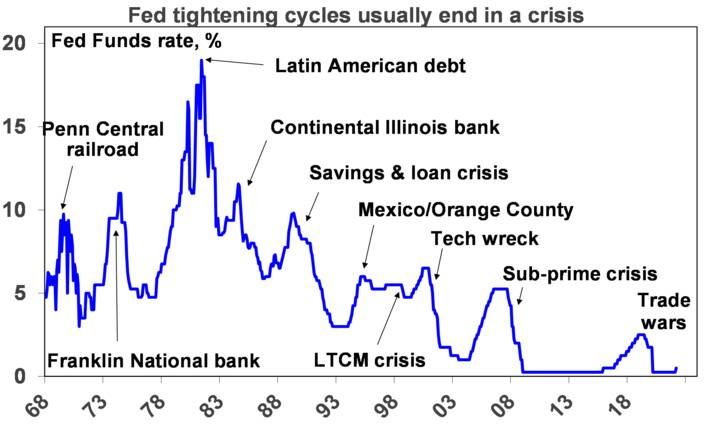

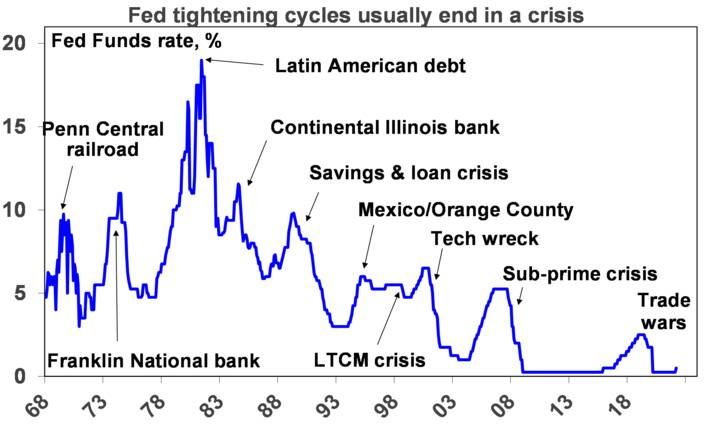

- The drumbeat of central bank tightening got louder with the Fed joining in. Its 0.25% hike was well flagged and the Fed was upbeat on the US economy which enabled shares to rally on the hike. However, the Fed was more hawkish than expected signalling another 6 hikes this year and 3-4 next year with the start of quantitative tightening as soon as May, all to bring inflation back under control.

Source: Bloomberg; AMP

- Historically Fed tightening cycles usually end in some sort of crisis (not all of which are the Fed’s making), but it’s very early days yet as monetary policy takes a while to become tight enough to bring on a recession which ends the cyclical bull market in shares (which is probably more of a risk for 2024 than 2022). The progression of rate hikes at every Fed meeting this year along with high inflation and the war in Ukraine add to the risks though which will ensure a continuing volatile and constrained ride.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

- The Bank of England also raised interest rates for the second time, but its commentary shifted dovish signalling that a further tightening “might be appropriate” which was softened from “likely” in February given the risks to the economy posed by the war. Taiwan’s central bank also raised rates for the first time in this cycle. And another rise in Canadian inflation points to another Bank of Canada rate hike next month.

- The RBA does not simply follow the Fed on rates and has diverged several times over the last 15 years, but with our economy now moving in the same direction as the US, albeit with lower inflation, expect it to start raising rates in June. The fall in unemployment to 4% in February, strong labour market indicators pointing to a further fall to 3.8% by June and probably 3.5% by year end – levels not seen since 1974 – and a plunge in underemployment all point to significant upwards pressure on wages growth. The very tight labour market combined with a steady stream of anecdotes of rising consumer prices all point to RBA rate hikes sooner rather than later. Even the RBA’s minutes now show the RBA seeing the risks for wages growth as skewed to the upside. We are now already at full employment and the RBA will likely have to revise up its inflation and wages forecasts. A May rate hike is possible after a likely blow out inflation report is released for the March quarter but given it will be in the midst of the election campaign the RBA will probably prefer to wait to June. So, June remains the base case.

Source: ABS, AMP

- Covid versus more stimulus in China. Although the numbers are comparatively low (eg, South Korea is seeing around 350,000 case a day) the surge in coronavirus cases in China and associated lockdowns in various cities including Shenzen and parts of Shanghai will put more downwards pressure on Chinese growth and add to global supply concerns. China’s problem is that its vaccines are reportedly not as effective against Omicron and its zero covid policy means it does not have a lot of immunity against Covid. Against this, with Chinese sharemarkets plunging earlier in the week Chinese policy makers responded with a stronger commitment to boost growth and financial markets and address property developers’ risks. The 2020 experience where Chinese growth briefly slumped then rebounded indicates investors should not ignore this.

Source: ourworldindata.org, AMP

- What would a Russian default mean? Short of a quick removal of sanctions which looks unlikely a default event almost looks inevitable sometime soon. However, short of a key player being heavily geared into Russian debt (like LTCM in 1998) it’s hard to see a default causing major problems. Investment funds globally are already divesting/writing down the value of their Russian debt (as in many cases it can only be sold at fire sale prices). The risk of financial instability flowing from a default though will be watched closely by central banks which are likely to inject short term liquidity into markets if needed. Argentina has regularly defaulted without major systemic financial problems globally. Of course it will mean that Russia will be frozen out of global debt markets – but then it is anyway.

|